Construction cranes climb into the sky and sprawl across the massive petrochemical facility that will turn a byproduct of fracked gas into plastic on the banks of the Ohio River, just outside Pittsburgh.

Even at a distance, from the car park of a cancer treatment centre on a nearby hilltop, Royal Dutch Shell’s 386-acre site is a behemoth. It will anchor yet more gas, plastics and chemicals infrastructure in the tristate region of Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia.

The plant would solidify demand for fracked natural gas and the ethane that comes with it out of the ground. It would make 1.6m tons of plastic and 2.2m tons of globe-heating carbon dioxide annually – roughly the same amount the city of Pittsburgh is trying to eliminate. The facility would also release hundreds of tons of toxic compounds into the air.

As global demand for plastics grows, the buildout of this industry threatens US progress on the climate crisis and clean air.

Opponents say the vast plastics industry will prolong fracking, even after power companies shift further towards renewable power, such as solar and wind. “To me, it’s so obvious that they are trying to lock us into fossil fuels,” said Terrie Baumgardner, a member of the Beaver County Marcellus Awareness Community.

At a time when scientists warn humans must stop pulling fossil fuels out of the ground and spewing plastics into the environment, natural gas drilling is booming in Appalachia and the ethane-to-plastics industry there is just getting started.

Photograph: National Geographic Image Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

In a tall office building on a hazy Pittsburgh day, Matt Mehalik, the executive director of a public health collaboration called the Breathe Project, slammed his hand on a table. “This region has been down this path before and we should know better,” he said. “I grew up in Pittsburgh at the time the steel industry unravelled. It has taken 30 years to recover.”

Dangerous air

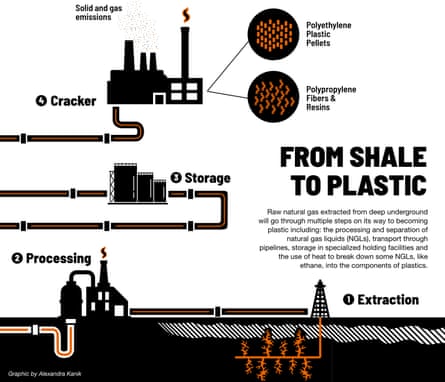

Opposed residents have myriad concerns. The Shell ethane facility, or “cracker” plant, would use extreme heat to turn ethane into ethylene, which becomes the polyethylene in plastic bottles, bags and food packaging. It will be fed by thousands of fracking wells that dot local communities, including next to day-care facilities and school bus stops.

Pipelines run under neighbourhoods that have previously been affected by explosions and fires. Trucks overwhelm the roads.

Residents opposing the ever-growing expansion say they worry about illnesses and dozens of cases of rare cancers they never saw in generations past.

Pittsburgh already has some of the most dangerous air in America. The city received a double-F rating from the American Lung Association for smog and particle pollution from fossil fuels. And Allegheny County, which includes Pittsburgh, has ranked in the top 2% for cancer risks from air pollution.

And a report by the Conservation Voters of Pennsylvania last year found that since 2007, companies profiting from fracking had spent nearly $70m lobbying the state government, in part to insist the method was safe.

“Fracking money has undermined the voice of the people in comparison to the voice of the desire for fracking in the region,” said Mark Dixon, a film-maker and activist.

The pro-business group the Allegheny Conference on Community Development has boasted the plastics boom could turn Appalachia into a petrochemical hub similar to the Gulf Coast. But there, Louisiana residents have long tried to draw attention to the stretch of communities between New Orleans and Baton Rouge known as “Cancer Alley”.

The conference argues its goal is to attract business and that government regulators are responsible for keeping residents healthy. A spokesman, Philip Cynar, said: “We have to think about the holistic approach … we can do a lot more for the overall benefit of the region if we have a good economy.”

The fear of health risks is misplaced, according to Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. In consultation with US regulators, it approved Shell’s air pollution plan in 2015. Allegheny County’s health department considered the effects of the plant’s releases of benzene, toluene, hexane, formaldehyde and ammonia – which cause cancer and other serious health problems. The department found the levels would be “well below the health-based risk value” for an individual.

Shell has said it designed the facility to “obtain the lowest achievable emissions.”

Aside from air pollution, the Shell plant will be as bad for global heating as putting a further 424,000 cars on the road each year. “It’s a huge paradox,” said Grant Ervin, Pittsburgh’s chief resilience officer. Oil and gas jobs pay well, even for people straight out of high school, he said. But the climate crisis puts humans “at the precipice of a public health disaster.”

Job creation

Republicans and Democrats have supported the Shell plant, saying it will bring work to an area that has been hit hard by a downturn in US-made steel and coal.

Shell says it will create 6,000 construction jobs in the short term and 600 over the longer term. It is unclear exactly how many will go to locals. State lawmakers offered the company a $1.65bn, 25-year tax cut, the biggest break in Pennsylvania history.

Republican legislators have proposed a package of bills to encourage the natural gas industry, including by speeding the process for permitting projects and providing huge financial incentives.

Pennsylvania’s governor, the Democrat Tom Wolf, inherited the project from a Republican predecessor and now supports it.

But the facility and others like it are antithetical to Wolf’s plans to shrink the climate footprint of Pennsylvania, the country’s fourth-largest emitter of carbon dioxide. He wants to cut carbon pollution in Pennsylvania 26% by 2025, and 80% by 2050. His Department of Environmental Protection said the state is requiring the plant to reduce its climate footprint as possible “to help ensure that economic development and environmental protection can go hand in hand.”

Pittsburgh’s mayor, the Democrat Bill Peduto, famously challenged Trump on climate change, saying Pittsburgh would abide by an international pledge to limit heat-trapping pollution, even if Trump would not.

But Peduto has stayed silent about the plant.

Construction continues

Hailed by Barack Obama as a “bridge fuel”, natural gas has become a nightmare for climate advocates. It has spurred a transition from coal, which emits twice as much carbon dioxide. But the bridge does not seem to be ending, and the natural gas production process leaks methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

The industry has continued to build wells, plants and pipelines – about 27% of natural gas in the US comes from the Marcellus and Utica shales under Appalachia. By 2040, the area will produce 37% of the country’s natural gas, according to the data firm IHS Markit.

Appalachia has wet gas, meaning it produces both the methane mixture that is used for power and stovetops and natural gas liquids, including ethane and propane. Drillers want a local market at which to sell them all.

Of the Democratic frontrunners for president, senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have pledged to ban fracking. Joe Biden, the former vice-president, has not.

But the Trump administration is supporting the build-out.

Ken Humphreys, a senior adviser for regional economic development at the US Department of Energy, said: “Broadly this is about creating the conditions for private capital to flow into the region.

Between 2018 and 2040, the US’s capacity for making ethylene and intermediate petrochemical products is expected to nearly double.

The energy department argues that global demand for plastic is rising, and it will either be produced in the US or in countries with more lax environmental standards.

Humphreys said there were 7,500 businesses within 300 miles of Pittsburgh, employing 900,000 people to make products that incorporated petrochemicals – most of which came from the Gulf Coast. Producing plastic locally would be more efficient, the department said.

Rare cancers

In Washington County, Pennsylvania, south-west of Pittsburgh, fracking well pads sit alongside neighbourhoods. One, called a super-frack pad because of its dozens of wellheads, sits in a valley next to the former coal community of Marianna.

A school bus stop overlooks the site and the children who wait there each morning live in brick homes that were built for coalminers and then abandoned.

Four counties in south-western Pennsylvania have been afflicted by a rash of rare cancers, including 27 cases of Ewing sarcoma over 10 years in a population of about 750,000. The bone cancer usually occurs in children and young adults.

A retired paediatrician, Ned Ketyer, said: “Ewing sarcoma is a nightmare for the families that are given that diagnosis, and certainly for the patients and also for the physicians that diagnose it. It starts very quietly but by the time the diagnosis is made it has deepened and spread.”

There are dozens of other rare cancer cases in the area too. The Pennsylvania Department of Health studied rates of the disease in two school districts and said there was no evidence of a cluster.

But people are still worried. Last week, 50 environmental advocacy and public health groups as well as hundreds of individuals signed a letter to the Pennsylvania governor asking him to attend a public meeting to hear their health concerns. The state’s epidemiologist attended instead.

The region has a toxic legacy that predates natural gas – including hundreds of years of coal-mining and agriculture pesticide use. But Ketyer said the cancers did not begin until fracking arrived.

Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection found the Shell plant’s hazardous air pollutants--which cause cancer and other serious sicknesses--“will not threaten public health and safety,” spokesman Neil Shader said.

Residents also worry about gas industry accidents. One September morning in 2018, Karen Gdula awoke to an explosion and flames shooting into the air from a 24-inch pipeline buried a few houses away. Her neighbours narrowly escaped with several of their dogs, but they lost their home, another dog and four cats in the fire.

Q&AWhat is the polluters project?

Show

The Guardian has collaborated with leading scientists and NGOs to expose, with exclusive data, investigations and analysis, the fossil fuel companies that are perpetuating the climate crisis – some of which have accelerated their extraction of coal, oil and gas even as the devastating impact on the planet and humanity was becoming clear.

The investigation has involved more than 20 Guardian journalists working across the world for the past six months.

The project focuses on what the companies have extracted from the ground, and the subsequent emissions they are responsible for, since 1965. The analysis, undertaken by Richard Heede at the Climate Accountability Institute, calculates how much carbon is emitted throughout the supply chain, from extraction to use by consumers. Heede said: "The fact that consumers combust the fuels to carbon dioxide, water, heat and pollutants does not absolve the fossil fuel companies from responsibility for knowingly perpetuating the carbon era and accelerating the climate crisis toward the existential threat it has now become."

One aim of the project is to move the focus of debate from individual responsibilities to power structures – so our reporters also examined the financial and lobbying structures that let fossil fuel firms keep growing, and discovered which elected politicians were voting for change.

Another aim of the project is to press governments and corporations to close the gap between ambitious long-term promises and lacklustre short-term action. The UN says the coming decade is crucial if the world is to avoid the most catastrophic consequences of global heating. Reining in our dependence on fossil fuels and dramatically accelerating the transition to renewable energy has never been more urgent.

Another neighbour, who was celebrating her birthday, had trouble convincing an emergency services operator that the pipeline had exploded until the operator heard the fire roar. The flames were so hot they melted a nearby transmission tower.

A second pipeline is under construction that will cross over the one that exploded. Gdula has been working with the construction company to make it safer for the neighbourhood. “My goal is safety,” she said. “We don’t believe we can stop them but we can do what we can to be safe.”

Global heating

Natural gas from shale – the type that is extracted with fracking – is expected to double in the US in the coming decades, mostly in the east, according to the US Energy Information Administration. And the energy department expects an enormous 20-fold surge in ethane production in the eastern US by 2025.

Scientists say to avoid catastrophe from rising temperatures, people must rapidly reduce their emissions from fossil fuels to net zero by 2050.

The world is already 1C hotter than before industrialisation, and it is on track to warm an additional 2C – worsening extreme weather and poverty and leading to rapidly rising seas.

The Center for International Environmental Law, a pro-environment group, estimates that by 2050 climate-harming emissions from the production and incineration of plastics could reach 56 gigatons per year, or 10-13% of the budget allowed for keeping temperatures from rising more than 1.5C.

There is no way of knowing how much a plastics hub in Appalachia will exacerbate global warming and offset the work of states and cities trying to cut heat-trapping emissions. The ethane boom will, however, stretch beyond western Pennsylvania into Ohio and West Virginia.

In nearby Barnesville, Jill Hunkler said she was driven from her home by fracking. As gas wells were constructed around her, Hunkler said she started to experience headaches, breathing problems, burning eyes and a metallic taste in her mouth.

Hunkler counts 78 producing wells within five miles of her house, according to data from FracTracker. “There’s just no respect for the local community’s health,” she claimed.

Bev Reed, a nursing graduate and intern at the Sierra Club, a grassroots environmental organisation, said the community had no say over whether the facility was built.

“We already know it’s not sustainable and that Appalachia has been pillaged and plundered and raped for pretty much as long as its existed,” Reed said. “We’ve seen enough and we deserve better.”