One afternoon in early June, graduation week in Charlotte, North Carolina, Dorothy Counts-Scoggins answers the landline phone and waits for an update on the white people who want to flee the local school system she was the first to integrate.

“What happened?” she asks me, her voice low, as if she already knows the answer.

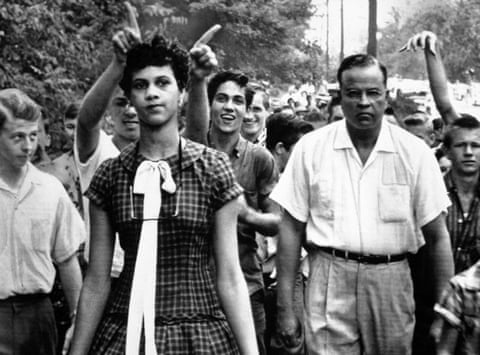

Counts-Scoggins is 76 and lives in the west Charlotte neighborhood where she grew up. The black and white photo that reshaped schools in the south adorns her wall. In the frame, it is 1957. She’s 15 and walking toward a previously all-white high school, her chin up and shoulders back, flanked by hunched-over white kids following her menacingly, their spittle soaked into the fabric of her checkered dress.

The next morning, she was on the front page of the New York Times under the headline Soldiers and Jeering Whites Greet Negro Students. James Baldwin saw the image and said it compelled him to return to the United States from France to write about civil rights in the south.

“There was unutterable pride, tension and anguish in that girl’s face as she approached the halls of learning, with history jeering at her back,” he later said. “It made me furious. It filled me with both hatred and pity. And it made me ashamed. Some one of us should have been there with her.”

Right there in the frame, the next generation of white hate was stalking the next generation of black dignity, right when the civil rights movement was starting to spread.

Counts-Scoggins went on to finish high school and college quietly, but then she dedicated her career to public education in her home city as a mentor, speaker and childcare services administrator. Her life’s mission, she has said over and over, is to “make sure no child ever goes through what I went through”.

But 60 years later, children are going through it again.

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system is now the most segregated in North Carolina: 55% of students would need to change schools for the district to achieve full integration. Charlotte welcomes 60 new residents every day; its allure is not country music or Spanish moss, as in other booming southern cities, but something subtle and less hip: the city is simply a comfortable place to live and raise a family. The diverse economy, with textiles and banking and farming, held up better than most during the Great Depression, keeping the population growing even in the worst years.

For all these reasons, Charlotte’s schools have been a weathervane for America’s relationship with public education for decades.

In 1957, it was Counts-Scoggins, striding toward Harding High School in a city that viewed itself as progressive, surrounded by shouts of “Go home, nigger”. In 1964, it was Darius Swann, a black six-year-old denied admission to the integrated Seversville elementary – inciting the lawsuit that led to a supreme court ruling in favor of bussing as a means to desegregate.

In the late 1990s, it was William Capacchione, a white parent, arguing that his daughter was shut out of a magnet program because she wasn’t black, resulting in a federal district judge ordering CMS to stop using race in student assignments.

And in 2018, it’s four dove-white suburbs asking for more “choice”.

A bill before the state legislature, HB 514, would allow these towns, each more than 77% white, to develop their own charter schools. If it becomes law, town residents would have priority admission, and kids from the rest of the county would be able to enroll only if seats remain.

It’s part of a deconstruction of school systems that’s already occurred in other cities – Detroit and New Orleans, for instance – and a trend that the US secretary of education Betsy DeVos would like to see continue nationally. Congress rejected many of her spending proposals this year, but DeVos’s goals were clear when she suggested adding $1bn for school choice programs and vouchers while cutting the US Department of Education by 5%.

Supporters of the North Carolina bill argue that charters provide students and parents with more options than traditional public schools systems, while expressing little concern for kids who may be left behind in a shrinking district.

For Counts-Scoggins, it feels like another thread being pulled out of her life’s work. She’s spent 61 years trying to walk out of that photo. She prefers to be called Dot Counts-Scoggins now, but it’s a regular occurrence for something to remind her of a time when her name went around the world as Dorothy Counts. She’s a part of a generation of civil rights activists who endured the abuses of the 1950s and 1960s, only to see a surge of repeat offenses late in life. She’s a living lesson, unlearned.

To her, this isn’t the standard debate over whether charters are as effective as traditional schools. It’s about wealthy towns crouching behind charters to pass a law that builds walls around white zip codes.

The North Carolina general assembly convened on 16 May; by Memorial Day, it was clear that the Republican majority had enough votes to make HB 514 law.

When she answers her phone that Wednesday in June, Counts-Scoggins is prepared for news that her telltale southern city will become an example once more – this time of a country chiseling away at the public education system for which she suffered.

“Did they pass it?” she asks.

“Yes,” I tell her.

The line goes silent for several seconds before she speaks again.

“I just can’t believe Charlotte is getting to that point,” she says. “It’s nothing but racism. You know that and I know that.”

Unlike Counts-Scoggins’s, my kindergarten class photo had 13 white kids and 12 black kids. I came through public schools in the 1980s in rural southern Maryland, where my mother was a first-grade teacher. Although we had our problems, our classes taught us to revere civil rights heroes. I moved to Charlotte six years ago to become editor of the city magazine, a job that introduced me to many of the region’s leaders. I was more nervous to meet Dorothy Counts than any of them.

We’ve since become friends. I’ve grown close to her brother, Howard, too. Counts-Scoggins laughs and says that she’s adopted me and my wife, Laura, who came through CMS, as part of her extended family.

When Counts-Scoggins tells me she sees racism, I don’t question it.

As kids, she and her three brothers spent summers at their grandparents’ house in the tiny town of Rowland, North Carolina, two hours east of Charlotte. Her grandfather was a barber and her grandmother a seamstress. They’d stopped for gas one day in the early 1900s, only to be approached by two white men who, unprompted, offered to help her grandfather set up a shop and business. Racism seemed like a distant affliction to Counts-Scoggins as she passed the summers lying on the floor, watching her grandmother’s foot thump on the sewing machine pedal.

The summer of 1957 was different. She was one of two Charlotte-area girls chosen to join 1,800 Presbyterians at the National Youth Assembly at Grinnell College in Iowa. As she unpacked her clothes, her roommate for the week, a white girl from Illinois, stared at her. Counts-Scoggins asked if something was wrong, and the girl admitted that she had never been face-to-face with a black person.

The girl asked Counts-Scoggins if she had a tail. She asked her if her skin rubbed off. Counts-Scoggins stopped her.

“Believe it or not, you and I are alike in a lot of ways,” Counts-Scoggins told her. They were friends by the end of the week.

A month later, her parents learned that she and three children at other schools would be the first black students to step into all-white public schools in Charlotte.

A group named the White Citizens’ Council chose Harding as the place they would protest. The temperature was already in the 80s on 4 September 1957, when the mob filled two city blocks on the west side of uptown.

At about the same hour, 750 miles away in Little Rock, Arkansas, armed state militia stopped another 15-year-old, Elizabeth Eckford, as she clutched a notebook to her chest while trying to enter Little Rock Central high school with eight other black students. No troops greeted Counts-Scoggins, but the crowd grew angrier each step she took. White boys in buzz cuts and plaid shirts filed in behind her and made faces that would remain stuck that way in photos. Others threw pebbles at her from behind a tree. One woman, a parent, skittered up behind the crowd and hollered: “Spit on her, girls! Spit on her!”

Inside, teenagers tugged on her dress and hurled erasers at her head, harassment that was unofficially sanctioned by teachers and administrators who didn’t stop it.

It remains Charlotte’s most disgraceful moment. Even the woman who shouted “Spit on her, girls!” later quit the White Citizens’ Council, saying: “I am ashamed of the white race.”

That night, though, Counts-Scoggins thought about the white girl in Iowa who asked if she had a tail.

“If they just get to know me,” she told her parents, “they’ll like me.”

But the Harding kids didn’t like her. The next Wednesday after school, boys heaved rocks painted like oranges through her brother’s car window. That night, she sat on the couch next to her parents as they told a news crew that it was too dangerous. They sent her to live the rest of the year with relatives in Philadelphia. Two weeks later, then president Dwight Eisenhower ordered federal troops to Arkansas to escort the Little Rock Nine into Central high.

On 3 September 1957, the day before schools opened, then North Carolina governor Luther Hodges asked for “voluntary separate school attendance”. Basically, the idea was that black parents should choose to keep their kids in black schools – for their own good, of course.

“Can these few citizens seriously believe that they are helping remove any real or fancied stigma from their race by placing their children in schools formerly attended only by white children?” Hodges said. “Where are the Negro leaders of wisdom and courage to tell their people these things? Have they none?”

School choice has advanced since then. But every iteration is underscored by a reluctance to commit to a public education system that benefits everyone. Throughout the 1960s, small, private Christian schools popped up across rural North Carolina – especially in the eastern part of the state, where some families still control land granted by King Charles II – as white parents shuffled their kids out of integrated public systems.

North Carolina’s legislature had bipartisan support to open the state to charter schools – public schools that run independently and are subsidized by private funding – with a 100-school cap in 1996. The appeal of charter schools seemed straightforward – tax money goes to the school instead of inflated administrations, and instructors have freedom from standardized testing. A decade later, the results were mixed.

As with most things that are inconclusive, charters became a partisan issue with plenty of gray space for politicians to manipulate. Republicans say they inspire innovation; Democrats say they undermine public systems.

One example is in rural Northampton county, North Carolina, where 26% of residents live in poverty and more than 70% of the student population is black. The charter school there, KIPP Gaston College Prep, consistently scores high. But the other 80% of the students in the county remain in underperforming traditional schools. A charter-school advocate, likely Republican, would note the single success; an opponent, likely Democrat, would note the overall failure.

Dorothy Counts graduated from an all-black girls’ high school, earned a degree from the historically black Johnson C Smith University, moved to New York, got married, and then came home as Dot Counts-Scoggins to live in a predominantly white suburb named Matthews.

By then, the Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education decision had helped make CMS a national model for desegregation. The Charlotte Observer called it the city’s proudest accomplishment. But not all parents were happy.

A woman knocked on Counts-Scoggins’s door one day, upset that her kids were being bussed from Matthews to a school in a predominantly black neighborhood. When the woman held out a petition she was circulating, Counts-Scoggins said: “You’ve come to the wrong house. I don’t think you know who I am.”

Parents like that eventually ended bussing in 1999, rocking the demographic makeup of the district. Within 15 years, a third of CMS schools were segregated by poverty, and half were segregated by race.

In September 2016, Charlotte’s inequities received national attention during a weeklong string of protests following the police shooting of Keith Scott, a black man, in a north Charlotte apartment complex.

“One cannot disentangle the state-sanctioned school resegregation that poor black students in Charlotte experience from the police killing of a black man waiting for his son to get off the bus from elementary school,” Clint Smith wrote in the New Yorker.

Eight months later, CMS took the first major policy action after the protests. The board approved a modest student reassignment plan that would affect only about 10% of the district’s 147,000 students. No children in Matthews would have to switch schools, but the mere threat of it made people there skittish.

State representative Bill Brawley, a Matthews Republican, introduced HB 514 that month.

Supporters say it’s not about race. They point to things like last year’s $922m school construction bond package that included little for the northern suburbs. “[HB 514] gives us an option to add capacity should CMS opt not to,” Huntersville mayor John Aneralla told me in May. “They will not add capacity unless pushed.”

The school board responded to HB514 in late August by doing the opposite, passing a measure to block future construction in the four suburbs unless they agree to a 15-year moratorium on municipal charters.

Regardless, opponents like Counts-Scoggins see capacity as an ornament hanging on a tree of a different concern, one more like what then-Matthews mayor Jim Taylor told the Charlotte Observer when the bill was introduced.

“I am pleased with the new proposed student assignment plan but the concern I have is that student assignment will come up again,” Taylor said in 2017. “We will be fine today, but there is no guarantee for the future.”

In 2006, Counts-Scoggins opened an email from a white man named Woody Cooper, admitting that he was one of the kids in the photo. He wanted to apologize.

They met for lunch at the now 67-year-old Open Kitchen restaurant near uptown. In the 1950s, white teenagers could eat in the restaurant’s dining room, but black teenagers ordered to-go plates from the back window. Cooper asked Counts-Scoggins if she could forgive him. “I forgave you a long time ago,” she said. “This is an opportunity for us to do some things for our children and grandchildren.”

They agreed to share their story with former Charlotte Observer columnist Tommy Tomlinson. The piece ran on the 50th anniversary of Counts-Scoggins’s walk, and the state press association named it the best story in North Carolina that year. From there Counts-Scoggins and Cooper did as many speaking engagements and interviews as they could.

Cooper got cancer a couple of years later. On a Wednesday in September 2010, Counts-Scoggins drove to a Huntersville hospice facility to say goodbye. She sat with him for two hours. Cooper never opened his eyes. She kissed him on the forehead and left. The next morning, Cooper ’s wife, Judy, called to say he was gone.

“Dot, I think he was waiting for you,” Judy said.

Counts-Scoggins has always been there. She’s told her story thousands of times all over the country. She’s a mentor at a high-poverty school. She’s part of the Women’s Inter-Cultural Exchange, an organization that “builds trust across race and culture”. This September, she’ll receive the United Negro College Fund’s Maya Angelou award for lifetime achievement. Next spring, she’ll be surrounded by children of all colors on a one-mile Unity Walk that will end at the old Harding high school.

But instead of talking about how far we’ve come, she talks now about recognizing mistakes from the past as they pop up again today.

In 2016, there were the Charlotte protests after a police shooting. Last year, there were white supremacists terrorizing Charlottesville, only a few hours north.

And then there was an event this spring, one that made headlines only in her family. Counts-Scoggins’s great-nephew, a brilliant fifth-grader who spends as much time with her as she did her grandparents, came home from school one day and said that a teacher told him that slavery wasn’t all bad.

She called the school and the administration and anybody who’d listen.

“What gives him the right to talk to any child about slavery like that?” she tells me. “I did not think after all these years I’d still be fighting this.”

Michael Graff is a writer in Charlotte