Recently, when friends have asked what I am working on and I’ve told them that I am reviewing a British photo-essay book called What Does a Jew Look Like?, they have reacted with a nervous giggle. This has sometimes been followed by “Wow!,” “Oy,” or an ominous “Uh-oh.” The uneasiness stems, I think, from the question itself, not its possible answers. What a Jew looks like has been a subject, indeed obsession, of Jews and non-Jews, of antisemites and Zionists, of novelists and artists, of Europeans and Arabs. The question is sometimes posed as a matter of aesthetics, but it is always fundamentally political.

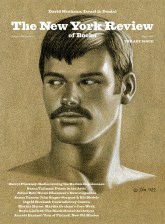

Keith Kahn-Harris and the photographer Robert Stothard, the British authors of What Does a Jew Look Like?, believe that the titular question is germane. Jews are a minuscule minority in Britain: they number fewer than 300,000 out of a total population of over 67 million. Too often, Kahn-Harris argues in his introduction, British newspapers illustrate articles on Jewish subjects with a stock picture of two “black-hatted, black-coated” Haredi Jews walking down a street, backs to the camera. No faces are shown:

They are mysterious, perhaps secretive, and women are invisible. Such Jews are made generic because they seem to be the “most” Jewish…. Only those who cannot be assimilated into “us” can truly represent “them.”

The Jewish community in Britain, though small, is hardly invisible. Jews are prominent in academia, journalism, medicine, and other professions. Indeed, Kahn-Harris notes, “Jews in this country have never been more visible, more spoken about and also more outspoken about themselves.” But as has been true so often throughout Jewish history, such visibility isn’t entirely welcome and can create, among the larger population, confusion, discomfort, suspicion, and resentment. In fact, charges of antisemitism rocked the Labour Party during the tumultuous five years, beginning in 2015, when Jeremy Corbyn was its leader. Since the Hamas attacks of October 7, the subsequent Israeli invasion of Gaza, and the furious worldwide protests the latter has prompted, Jewish visibility—and antisemitic tropes and attacks—have vastly increased.

“Are Jews a religion, an ethnicity, a nation or something else?,” Kahn-Harris asks. “Are Jews ‘white’? Are Jews Zionists? Are Jews rich? And what do we do with Jews who…do not fit into any existing category?” After several thousand years, Jews remain, it seems, a puzzlement.

To counteract stereotypes, What Does a Jew Look Like? presents a series of stately color portraits accompanied by brief testimonies from each subject. The book aims to complicate ideas about Jews and Jewishness, which will do nothing to counter antisemitism but is not in itself a bad thing.

And so we meet Dena from South London, a biracial woman who looks to be in her late teens. (The book provides no ages or last names.) Her frizzy black hair is held back by a headband; she tilts her head as she looks at the camera, perhaps suggesting a somewhat quizzical attitude toward the book’s project. Her green shirt, she tells us, denotes her membership in the youth group Noar Tzioni Reformi, or Young Reform Zionists. The daughter of a Ukrainian-Russian Jewish mother and a Nigerian Christian father, Dena describes herself as a “Liberal Jew…striving for equality.” She attends shul each Saturday. “I could see how it might be surprising for some people that I’m Jewish,” she says. “In the media Jews always look one way, with the big noses and stuff.”

The ultra-Orthodox are the fastest growing group among British Jews. Yidel, from Stamford Hill in London, looks to be in his mid-thirties; he sports a yarmulke, a trim beard, and payot. His calm yet slightly wary expression lends this picture its air of placid certainty. Yidel tells us that he is a member of the Bobov Hasidim: “Compared to some of the [other Hasidic groups], it’s quite neutral and non-specific in terms of its impact on everyday life.” He is a modern man, owner of an advertising business, but he’s a traditional man, too: “I want to raise my children the way I was raised.” He speaks Yiddish and English at home.

In contrast to Yidel’s tranquility, Rio, from Leeds, stares at the camera pugnaciously, as befits a man who has placed himself before a poster of the rock band Damn Vandals. He looks like a tough guy, with a scruffy beard, a partly shaved head, an earring, and tattoos (neck and arm). Rio was a teenage rebel, “oblivious to Judaism” until, as a young adolescent, his mother took him on a trip to Auschwitz. Then he began to study the Shoah in school and to listen to the stories told by his grandfather, who had been shipped to Siberia rather than to a death camp: “Hardly a consolation prize but ultimately the difference between survival and not (his parents weren’t so lucky though).” Rio avers that he is “totally irreligious.” But he recently lit a menorah at home: “After all, a lack of faith made no difference to the Gestapo or the KGB.”

Advertisement

The series continues: Rachel, a Holocaust survivor from what was then Czechoslovakia; Yael, whose Iraqi father immigrated to Israel as a child; Elliot, a gay man whose parents fled Iran’s Islamic Revolution. He regrets that, as a child of the diaspora, “I’m not as educated and experienced in the 2,700-year-old Iranian Jewish culture as I want to be.”

The childlike phrase “people who look like me,” which can be invoked with regard to anything from political representation and hiring practices to museum curation and journalism, seems omnipresent these days. In The New York Times the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah described the phrase, and the phenomenon it represents, as a “fervor.” This presumably left-wing version of tribalism bears an odd but unmistakable resemblance to that of right-wing populist movements; both rest, as the philosopher Susan Neiman argues in her recent book Left Is Not Woke, on the premise that “you will only truly connect with those who belong to your clan.”1

The “looks like me” paradigm implies that appearance can accurately reflect, or even predict, experience, values, personal qualities, and ideas. Yet the most oppressive, indeed racist, systems—slavery, colonialism, Jim Crow, South African apartheid—rested precisely on the premise that those who share a physical appearance (more or less), or share membership in an ethnic or racial group, are essentially the same and constitute an undifferentiated mass. The denial of individuality is foundational to such regimes and to their maintenance of power. (The Taliban’s imposition of the burka, which obscures a woman’s face, is a contemporary example of this strategy.)

The insistence on individual recognition was central to the cry “Say Her Name!,” which rang out after Breonna Taylor’s killing in 2020; protesters demanded that the singularity, which is to say the dignity, of her unique life be recognized. Similarly, the Tunisian-French Jewish writer Albert Memmi noted in The Colonizer and the Colonized (1957) that the negation of particularity was a crucial aspect of colonialism: “The colonized is never characterized in an individual manner; he is entitled only to drown in an anonymous collectivity.”

It is the complication of identity—the antithesis of anonymity—that is the real contribution of What Does a Jew Look Like? It’s not just that these Jews don’t look the same, which is, in the end, trivial; it’s that, even if they did, they aren’t the same. This is especially true when it comes to intra-Jewish political conflicts, which are famously disputatious.

Events in England—and in Israel-Palestine—are interpreted by these subjects in starkly different ways. Fiona, from Brighton, avers that her Zionism informs rather than contradicts her support for Palestinian rights. Richard, a founder of the left-wing Pluto Press, belongs to a small anti-Zionist group within Labour. The second intifada, notorious for Palestinian suicide bombings and ferocious Israeli air strikes on the West Bank and Gaza, reinforced both his Jewish identity and his anti-Zionism. Paul, a realtor, was radicalized by the Gaza conflict in 2008, though in the opposite way; he sees his work with the Zionist Federation “as a continuation of being a soldier.” Adrian , a former student radical who wears a prayer shawl, opposes the death penalty and boycotts of Israel; Aron, who sits in front of a Patrice Lumumba poster, organized a “Kaddish for Gaza” in 2018. I am certain that, were we to interview these subjects today, we would find both a heightened sense of unity and more acrimonious divisions. That has been the paradoxical effect that Hamas’s terrorist carnage, the staggering death toll from Israel’s assault on Gaza, rising antisemitism, and the messianic-racist Netanyahu government have had on Jewish communities, families, and friendships.

What a Jew—or, rather, an Israeli Jew—looks like has become, oddly, a focus of attention, especially among some parts of the American left. In this view, Israelis are “white” and Palestinians “people of color,” and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict replicates the template of racial justice movements in the United States. The American tendency to reduce political questions to ones of race and skin color—which is both understandable and facile—has been transposed to a national-religious struggle in the Middle East. The US Campaign for Palestinian Rights and Jewish Voice for Peace describe Zionism as a form of “white supremacy.” The editorial board of The Harvard Crimson enthusiastically endorsed a “colorful” campus “Wall of Resistance” that defines Zionism as white supremacy as well as racism, settler colonialism, and apartheid. Israel is, however, one of the world’s most multiethnic countries; an estimated half of Jewish Israelis are descended or emigrated directly from the Arab countries from which they fled or were expelled. Far more Jews have immigrated to Israel from Morocco, Iran, and Iraq than from Germany, Hungary, and France. (The journalist Matti Friedman has dubbed Israel “Mizrahi Nation.”) Palestinians, too, are diverse and exhibit a range of skin colors and physical characteristics.

Advertisement

In some ways the attempt to transform the Israeli–Palestinian conflict into a white-and-black issue is comprehensible. Once one form of moral harm—racism, colonialism, patriarchy, antisemitism—is taken to be exemplary, there is a great temptation to transform it into the paradigm of all harm. But rather than strengthening arguments or movements, this kind of reductionism inevitably distorts them. To view any one form of oppression as the ur-evil that necessarily underlies all others is a form of parochial projection. Rather than enlarging one’s worldview, it results in a radical simplification.

A glaring example of this tendency was a 2021 article by the Israeli academic Nimrod Ben Zeev in the well-respected journal Middle East Report, which sought to explain the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in primarily racial terms. Ben Zeev offered valuable insights into the inequalities that existed among Ashkenazi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, and Arabs in the British Mandate period. He astutely observed, “As racial thought invariably does, it collapsed the variety within the groups supposedly represented into monolithic, discrete fictions.” But he argued that “race and imperialism” have “always…defined” the Zionist project, and he framed his arguments within W.E.B. Du Bois’s well-known observation: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” This was an astoundingly prescient argument when Du Bois formulated it in 1903; it presaged the anticolonial movements of the twentieth century that would transform the map, and the political realities, of the world.

But according to Ben Zeev, the twenty-first century presents few new challenges: the color line, in Israel as elsewhere, “remains a defining feature of the present.” Yet it is striking how few of today’s conflicts are centered on race. Putin doesn’t hate the Ukrainians because of their race or skin color. Conflicts in Africa that have killed millions—think of South Sudan, Somalia, Congo—are not predicated on either race or color. Nor are the crises that roil the Middle East. The competition between Iran and Saudi Arabia (yes, still), the persecution of the Kurds and Yazidis, the civil wars in Yemen and Syria, the often deadly strife between Sunnis and Shias, the determination of Iran to eliminate Israel, the current war between Israel and Hamas: all are national, political, ethnic, or religious—and sometimes involve a lethal combination of those factors. In most of these conflicts, the antagonists look like brothers. There is overwhelming evidence that it is quite easy to hate people who look like you.

David Serry, a prolific though amateur photographer, was born in Jerusalem in 1913; his parents and their families were among the first wave of Yemeni Jews who emigrated to Palestine in 1882. His images exude what I would call the syntax of optimism—the Zionist negation of the despair that has characterized so much of Jewish history.

Serry concentrated, though not exclusively, on the Yemeni community in Mandatory Palestine and, then, Israel. His photographs reveal a generational divide. Many of his older subjects look as if they stepped directly out of the Ottoman era. In a 1932 portrait a woman named Romiyah Nadav smiles at us as she sits on a divan covered in a richly patterned kilim; a striped rug, patterned pillows, and another kilim adorn her room. Her head and neck are swathed in a white headscarf; her long, elaborately patterned dress drops to her ankles; her black shoes are scuffed. In a 1950 photograph an elderly bearded man, wearing what looks like a turban, rides a donkey down a Jerusalem street; he’s a milkman, carrying a large metal jug and a long stick.

Ah, but the younger generation is different. The young women have dispensed with headscarves; their dark hair is fashionably bobbed; their formfitting dresses up to date; even their knees sometimes show! More than that: they look happy. One lounges, resting on her elbows, in a halter bathing suit and high heels on the Tel Aviv beach in 1940; she turns her head to the camera to smile slyly at us. Young men are car mechanics, construction workers, farmers. Time and again, Serry concentrates on sports and physical prowess: here is the muscular, healthy “new Jew” that Zionism aimed to create in refutation of the supposedly feeble Jew of the diaspora.

So what does a Jew look like in David Serry’s photographs? Many look like poor people of tradition who had lived in the Arab world for thousands of years; they are deeply rooted in the ancient rituals of their past and their people. The poverty etched onto their weary, creased faces suggest the hard lives they have lived. (They don’t look, to me, much like white supremacists or settler colonialists.) There is a solemn dignity to these portraits; Serry is offering a familial respect. Yemeni immigrants, viewed as culturally backward by other Israelis and by the state, would subsequently face harsh discrimination in jobs, housing, and education. But Serry captures young Yemeni Jews in a moment of unprecedented liberation—from centuries of political powerlessness, from persecution, and from the shackles (both religious and cultural) of the past that their elders treasured and still embraced.

What a Jew looks like became the leitmotif of the Documenta art exhibition in Kassel, Germany, two years ago and led to its implosion. As the New York Times art critic Jason Farago reported, “It began with a calumny; it ends with a crackup.” The exhibition, one of the art world’s largest, wealthiest, and most influential, was curated by the Indonesian group Ruangrupa, which invited contributions from other collectives, many based in what is now called the Global South. Several exhibitions from a variety of countries displayed antisemitic tropes; in these, what Dena from South London called “the big noses and stuff” played a starring role, as did Nazi references.

When the fair opened in June, its first crisis involved the Indonesian collective Taring Padi, which displayed an impossible-to-miss, nearly sixty-foot-long agitprop mural called “People’s Justice.” Its subject is the murderous Suharto dictatorship, the resistance to it, and the many foreign governments that aided the regime. (In this, Israel had a very small part.) It shows two Jews. The first is a pig-faced soldier with “MOSSAD” printed on his helmet, a red neckerchief with a Jewish star, and a belted uniform that recalls those of Nazi soldiers; behind him is an Orthodox Jew with payot, fangs, bloodshot eyes, and a hooked nose. He munches a cigar—in George Grosz’s work, a symbol of the venal Weimar plutocrat—and wears a black derby hat marked “SS.” Other images in various exhibitions included Israeli soldiers depicted with bulbous noses with monkey-like faces, or as masked robots. Also shown were The Tokyo Reels, Palestinian propaganda and training films from the 1960s to 1980s that illustrated the “anti-imperialist solidarity” between Japan and the Palestinian movement. They were collected by Masao Adachi, a former leader of the Japanese Red Army, whose terrorist acts included the machine-gun massacre at Israel’s Lod airport in 1972. A festival committee of cultural experts urged that the films be canceled because they glorified terrorism and equated Israel with Nazi Germany. However, the screenings continued.

I tend to be extremely sympathetic to free speech arguments; artists have a right to create, and to show, repellent—even racist or threatening—images. (As a practical matter, though, Germany has no First Amendment, and antisemitic images that are considered “incitements of hatred” are illegal there.2) What interests me, though, is the puzzling plethora of Jewish—or, one might say, anti-Jewish—images at the fair, and the startling lack of any countervailing ones. Just when the furor over one image had almost subsided, another popped up, like a crazily energetic jack-in-the-box that couldn’t be suppressed. A specter was haunting Documenta: the image of the Jew.

The representation of Jews in “People’s Justice” provoked an outcry among the press and some viewers; the mural was quickly removed. Far from objecting, Ruangrupa and Taring Padi apologized for the caricatures in written and oral statements, including to the Bundestag. “We collectively failed to spot the figure in the work, which is a character that evokes classical stereotypes of antisemitism,” Ruangrupa wrote, speaking for both groups. “We…are shocked that this figure made it into the work in question.” A sense of bewilderment pervaded these explanations; one member of Taring Padi asked, “How did this happen? How didn’t we see this?” Both groups denied that they are antisemitic.

Some have considered the innocent, surprised dismay of these statements to be disingenuous. But I believe the Indonesian artists, and I am grateful that they exposed the heart of the matter. Indonesia has a population of more than 270 million, of whom over 85 percent are Muslim; its Jewish community numbers approximately one hundred. It does not recognize the State of Israel. It is quite likely that most, and perhaps all, the members of Ruangrupa and Taring Padi had never met a Jew. Somehow, though, the image of the Jew as a symbol of prime malevolence had permeated their collective unconscious.

This is puzzling but not inexplicable. As the historian David Nirenberg showed in his disturbing, brilliant book Anti-Judaism (2013), a society doesn’t need any actual Jews in order to imagine—and be obsessed with—who they are, how they look, and what they represent.3 For thousands of years, Nirenberg argues, Jews and Judaism have been used to explain a baffling array of contradictory phenomena including tyranny and revolution, carnality and intellectualism, capitalism and communism, insularity and cosmopolitanism, backwardness and progress. Jews in general and Israel in particular are a main prism through which otherwise disparate people conceptualize the world’s injustices. This is what the Yellow Vest nativist in France, the far-right nationalist in Poland and Hungary, the white supremacist in Charlottesville, and a section of the global left have in common. As Nirenberg noted, the conviction of the ancient Egyptians that Jews are enemies of all peoples and gods would remain “remarkably stable” over millennia.

At Documenta, the portrayals of Jews and Israelis nodded to modern politics and history, and especially to the indisputable wound of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. But the images’ iconography, and certainly their ethos—the ubiquitous Jew as greedy, heartless, repellent, feral—can be found in centuries of Christian paintings, drawings, and engravings (and secular ones, too). The association of Jews with iniquity was not created by the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, which is especially, catastrophically, blood-drenched at the present moment. On the contrary, depictions of that conflict have easily incorporated, and unthinkingly reproduced, preexisting tropes. (Accusations that Israelis harvest organs from dead Palestinians—a modern version of the old blood libel—now circulate.) And the Documenta artists’ repeated references to Nazism were not a reflection on, or engagement with, the agonies of the Shoah but rather a lazy and ignorant exploitation of it.

Many political writers and activists have noted that oppressed peoples often absorb the hateful vision of themselves, and especially of their physical appearance, created by those who wield power over them. Toni Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye (1970) exposes the power of racism through the story of a young, unloved black girl whose desire to be white, to look white, is a major factor that drives her to insanity. In an essay on the killing of Tyre Nichols by five black Memphis policemen last year, the journalist Jelani Cobb reminded readers that the cry “Black is beautiful” was directed not at whites but at black people “who had never considered the possibility that those two adjectives could coexist.”

Albert Memmi—who was simultaneously an anticolonialist, a socialist, and a Zionist—repeatedly analyzed the ways that colonized peoples, including Jews, internalize contempt; a chapter of his 1966 book The Liberation of the Jew is entitled “Self-hatred.” Memmi was born in 1920 and grew up in extreme poverty just outside the Jewish ghetto of Tunis. He pointed out that when it comes to physical appearance, a consistent “Jewish type” was a myth. In Portrait of a Jew, his classic study from 1962, he writes, “A separate Jewish race is an absurd concept.” A Polish Jew and an Iraqi Jew don’t necessarily look anything alike.

But a fantasy of shared characteristics—“the classic and unitary description”—indisputably existed: in this view, the Jew was short and swarthy, with dark curly hair, full lips, a large nose, and prominent ears. And although Jews share no single biological origin, Memmi described a colonized physique that was common among the ghetto’s inhabitants: “It is not surprising that oppression should leave its mark on the body.” Poor Jews shared with their poor Muslim neighbors “physiological misery, undernourishment and disease…. We were the same sickly, undersized individuals—either dark and shriveled like insects…or else unhealthily corpulent and yellow, billowing with obesity.”

It can be a Herculean task for the powerless to excise the Other’s picture of them. Memmi wrote of the “complexity of the Jew’s connection (like all oppressed persons) with the image non-Jews suggest of him. One thing is certain, he does not confine himself solely to denying it.” And here again—as it did at Documenta—the so-called Jewish nose makes a major appearance. “When a Jew has a big nose, it is as if he wore a permanent mark of his being a Jew in the middle of his face,” Memmi lamented.

That is to say, not the nose of the Jew he is, but the nose of the Jew people expect him to be. That poor nose…is here swollen with all the supposed Jewishness of its possessor. At once, as is the case with the Negro’s color, the Jew’s nose becomes the symbol of his misfortune and his exclusion.

For Memmi, Jewish shame was a psychological and existential problem, but one that only political self-determination could resolve. Most of all, he argued that the fixation on Jewish appearance is a sublimation of an unhealthy fascination with the Jewish people itself. Concept precedes anatomy: “It is the idea people have of the Jew that suggests and imposes a certain idea of Jewish biology.”

A recent event in Britain perfectly illustrates Memmi’s insights. Last April the apparently ever-fascinating question of what a Jew looks like—and the political implications that one can supposedly draw from the answer—emerged again, throwing the Labour Party into yet another crisis.4 Writing in a letter to the Observer, Diane Abbott, a Labour MP and Corbyn ally, argued that because Jews are a type of “white people,” they have never been victims of racism, for they “were not required to sit at the back of the bus” and “there were no white-seeming people manacled on the slave ships.” But Abbott allowed that Jews have undeniably experienced something called “prejudice”—as do “redheads,” she wrote.

This made me think that the next time someone wonders “What does a Jew look like?,” your first, best, and perhaps only response might be, “Why in the world do you care?” Or you might simply reprise Memmi’s query: “What is that Jewishness which gives the biology of the Jew significance?… What is the meaning of that picture of the Jew?”

-

1

See Fintan O’Toole, “Defying Tribalism,” The New York Review, November 2, 2023. ↩

-

2

See Susan Neiman, “Historical Reckoning Gone Haywire,” The New York Review, October 19, 2023. ↩

-

3

See Michael Walzer, “Imaginary Jews,” The New York Review, March 20, 2014. ↩

-

4

See Geoffrey Wheatcroft, “Bad Company,” The New York Review, June 28, 2018. ↩