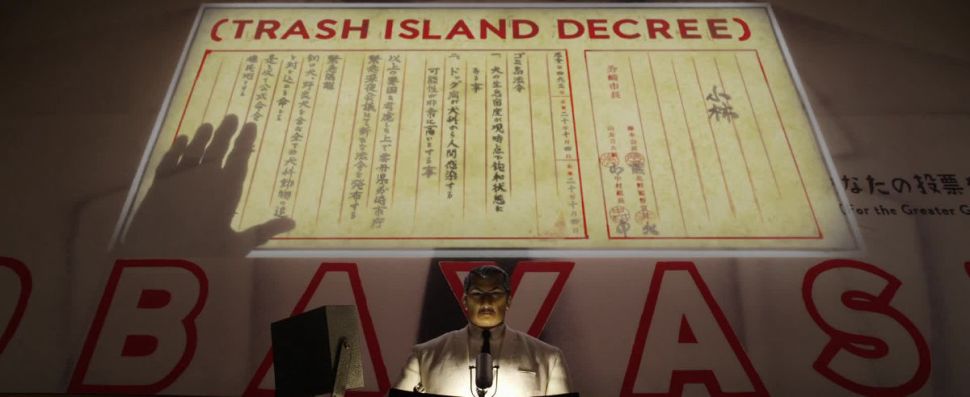

Apparently Wes Anderson is a political filmmaker; he’s just as surprised as you are. His latest stop-motion picture, the beguiling Japanophilic retro-futuristic Isle of Dogs, opened the Berlin International Film Festival last week with a surprisingly topical tale of the corrupt (and cat-loving) mayor of fictional city called Megasaki who exiles an entire species to a garbage dump called Trash Island. A government leader stoking prejudice and promoting deportation—seems a bit on the nose, especially for a director better known for eccentric characters in fastidiously hermetic worlds.

“The world changed while we were making this story,” Anderson said during a masterclass overlooking the Brandenberg Gate. “Politics became a bigger issue.” Isle of Dogs follows 12-year-old Atari Kobayashi, the nephew to and orphaned ward of the Mayor who secretly escapes to Trash Island to track down his faithful dog Spots. And in doing so, Atari gets wrapped up in the larger scandal of his uncle’s disinformation campaign to control the masses and hide the truth.

Anderson and fellow screenwriters Jason Schwartzman and Roman Coppola conceived the idea more than four years ago, long before the Trump presidency, and never envisioned their movie as anything more than a witty, heartfelt adventure about a boy and his dog. But even timeless tales can deliver a shock of urgency in the right place at the right time.

But Anderson was far from the only director making oblique, or even overt reference to the ugly sentiments that drive xenophobia. The festival also unspooled Erik Poppe’s much more confronting film U – July 22, a chilling Norwegian movie about the 2011 massacre on Utøya Island where far-right extremist gunman Anders Behring Breivik murdered 68 summer campers and wounded more than 100 others. The camping trip, organized by the youth division of the Norwegian Labor Party, was a target because of Breivik’s hatred towards the ruling government—including its liberal immigration policies.

What makes the film so powerful is its remarkable restraint, deftly sidestepping exploitation by almost never showing the killer, let alone any of the murders. Wisely eschewing any blood-soaked scenes, this is a film about the experience of living through trauma, being terrorized by the incessant sounds of gunfire, and the bloodcurdling screams of fellow students. Invisible horrors stay just beyond the frame, although scattered bodies on the ground are proof enough of the carnage.

When we do see Breivik (who goes unidentified in the film), he’s a blurry figure in the background as teenagers flee hysterically into the foreground. Poppe made sure that the individuals he depicts are not attempting to replicate the victims, but instead are inspired by interviews with the survivors, as a way to remain as respectful as possible to the horrific event. His guide through this living hell is Kaja (Andrea Berntzen), a straight-laced young teen desperate to find her sister, whose sense of duty and altruism makes her detour from one camp mate to the next, trying her best to help, to calm and to soothe, despite the hopelessly nihilistic experience of facing such blind, intolerant rage.

Jan Gebert’s documentary When the War Comes is a sobering documentary co-produced by HBO Europe that depicts a D.I.Y. paramilitary group in Slovakia marching around promoting “pan-Slavism” and devoting weekends to boot-camp training sessions. The all-white Slovak Recruits, as they call themselves, are comprised mostly of teenagers, and are a direct result of a climate where politicians around the globe are becoming more tolerant of anti-immigration hate speech. “It really reflects what’s going on in Europe right now,” said Gebert in a post-screening Q&A session, name-checking the current autocratic rulers of Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland—not to mention Donald Trump. “This is about the rise of Fascism and people doing nothing. This is how all that shit starts.”

The Berlinale is always haunted by history, since its current Potsdamer Platz locale was originally a no man’s land bifurcated by the Berlin Wall, and the former site of Hitler’s bunker is only a few hundred meters away. But this year, the festival feels more charged than usual with cinematic stories of xenophobia, tribalism and intolerance.

Showing how those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it, Christian Petzold, director of the universally acclaimed WWII-era mistaken-identity drama Phoenix, debuted his less acclaimed WWII-era mistaken-identity drama Transit. The twist this time is that Petzold places his 1940-set thriller in the here and now: his protagonist, a man fleeing Paris for Marseille and hopefully another country before the invading Nazi forces arrests him, moves through a present-day milieu of immigrants and transients. It’s a bold gesture to conflate world war displacement with modern refugees, although Petzold doesn’t quite follow through on the concept and ends up muddying his thematic aspirations with abstractions instead of emotions.

Far more cinematically successful is the startling drama Styx, Wolfgang Fischer’s hair-raising nautical adventure about a woman on a solo yachting expedition from Gibraltar all the way down the length of Africa to Ascension Island, the locale of Darwin’s wildly successful botanical eco-experiment to turn volcanic desolation into a verdant Eden. The impressively capable skipper, an affluent female doctor named Rike (Susanne Wolff) whose complete command of the ocean helps her literally weather a fierce Atlantic storm, faces another type of crisis when her boat passes by a fishing trawler teeming with refugees.

Imagine the Robert Redford survivalist sailing story All is Lost crossed with the Oscar-nominated humanitarian crisis documentary Fire at Sea and you’ll get a sense of Styx. When Rike makes an emergency call to the Coast Guard, she’s told to steer clear of the refugees at all costs and that help is on its way. But after 10 hours, help never arrives. And when she calls a nearby tanker for assistance, she’s told in no uncertain terms that geopolitics forbids intervention. “I could lose my job,” says the freighter’s captain.

Its hellacious mythological moniker notwithstanding, the film wrenchingly captures that Stygian sense of hopelessness inherent in her predicament. And the situation only gets more complicated when a young boy boldly jumps ship and swims over to her yacht, barely alive and suffering from dehydration, lacerations and chemical burns. Styx presents an unwinnable situation with all the right modulations, and its climax serves not only as a cry for help, but also as an act of defiance.