If you’ve been waiting for the right moment to break out your Aloha shirt for the summer, it’s finally here. At the New York Botanical Garden (N.Y.B.G.), an exhibition featuring the flora of the islands alongside rarely seen works by the OG flower painter Georgia O’Keeffe offers a tropical escape without ever having to leave New York City. And just like that tacky tee-shirt you love to parade around in at barbecues, “Georgia O’Keeffe: Visions of Hawaii” is cute but a little culturally complicated.

The extensive tropical floral installations in the Garden’s Enid A. Haupt Conservatory are inspired by a series of works O’Keeffe painted in 1939 while on a nine-week corporate sponsored trip to Hawaii, when the Hawaiian Pineapple Company—now known as the behemoth produce supplier, Dole—commissioned her to create images for their ad campaigns. Of the 20-odd resulting works, 17 are also on view, reunited in N.Y.B.G.’s art gallery. This is the first time they’ve been shown together since 1940, when they were exhibited to critical acclaim at New York’s An American Place, the gallery owned and operated by O’Keeffe’s husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz.

However inspiring for O’Keeffe, who was by then already known for her pastel desert landscapes and suggestive close-up paintings of flowers, the trip to Hawaii was by all accounts a bit of a wash in terms of recreating the islands’ “authentic” splendor. Although the exhibition lauds the artist’s uncanny ability to capture the essence of a place, many of the plants O’Keeffe recorded were not native to Hawaii, something Todd Forrest, the garden’s Vice President for Horticulture and Living Collections is quick to point out.

“What O’Keeffe ended up painting a lot of were species that had been introduced over the course of centuries,” he said, explaining that the artist captured mostly ornamental and agricultural transplants, like bougainvillea and red ginger. So, instead of showing off Hawaii’s natural wonders, N.Y.B.G. tries to “present her experience of the islands as a way of underscoring the complex environmental history of Hawaii,” Forrest said.

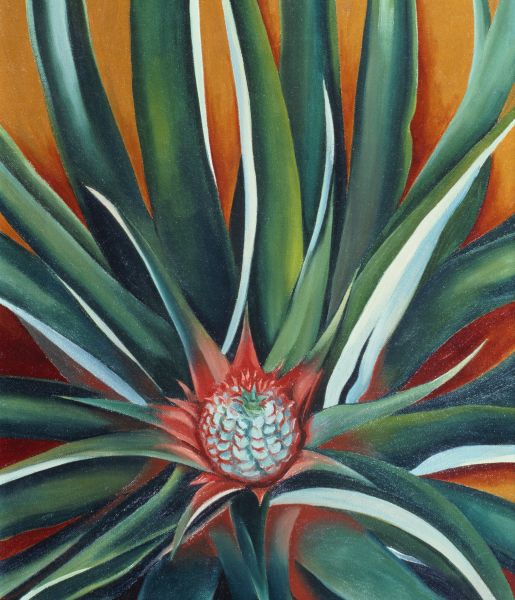

A complicated horticultural history it is, indeed. Even the pineapples the artist was supposed to be painting for Dole originated elsewhere. In fact, the first mention of them on the islands is from the late 18th century by a Spanish sailor credited with introducing mangoes and citrus to the region as well. But despite their perpetual propagation there, O’Keeffe didn’t do so great at painting those pesky prickly fruits, either.

The Hawaiian Pineapple Company was nonplussed when, after more than two months exploring the islands, she returned to them well past deadline just two paintings, Heloconia, Crab’s Claw Ginger and Papaya Tree, ‘Íao Valley, Maui, both of which are handsomely colorful and boldly graphic, (and on view in the N.Y.B.G.’s exhibition). But neither have a pineapple in sight. A baby pineapple was rush delivered from Dole’s plantations to the artist’s door in New York, with a firm entreaty to paint it ASAP. The eventual finalized ads with her artwork ran in numerous publications including the Saturday Evening Post and Woman’s Home Companion, archival issues of which introduce the entire art portion of exhibition, as if by way of nodding to the slanted view the artist was able to glean from her sponsored trip.

To be sure, “Visions of Hawaii” is as much about how O’Keeffe saw the islands as it is how she, and we, have been trained to see it, as an untouched paradise ripe for picking by a capitalistic society hell-bent on making a profit off the land and the people who tend it. The artist’s arrival on the islands was at the front end of the mid-century fetishiztion of tiki culture in America, which only intensified after Hawaii was devastated by the Pearl Harbor bombing. That was after years of summarily being ignored by the U.S. government as a long-time territory (it was added as the 50th state in the union in 1959, evidently once it had proven a popular enough tourist destination).

Additionally, by the time O’Keeffe made the journey to Hawaii, the ecological changes that ensued from the agricultural production of pineapple, mango and sugar had decimated the native plant species for over a century. “Today, habitat loss, environmental change, the introduction of invasive species, and other anthropogenic changes threaten an estimated 50 percent of the native plants of Hawaii,” Marc Hachadourian, N.Y.B.G.’s director of the Nolen Greenhouses, told Observer. “We and other conservation organizations are doing everything we can to save them, including preserving habitat and propagating wild plants for re-introduction as part of this exhibition.” These environmental issues could have stood to be fleshed out more fully and clearly in N.Y.B.G.’s exhibition of the beloved American artist’s work—there are already too many hackneyed representations of the state (see: white girl in a grass skirt at a luau in Connecticut) to risk assuming audience members will make these links themselves.

But the continual eradication of Hawaii’s natural environment is at least better addressed in the floral installations on the Garden’s grounds. The N.Y.B.G. horticulturists have raised stunning specimens of red and white hibiscus, Hawaiian-lily, and other native species not formally listed as endangered (federal laws outlaw the removal of endangered plants from the wild and the transport of endangered species across state lines, prohibiting seeds from making it to New York). They serve as important, living touch points that help tell the larger story of the vanishing Hawaiian flora.

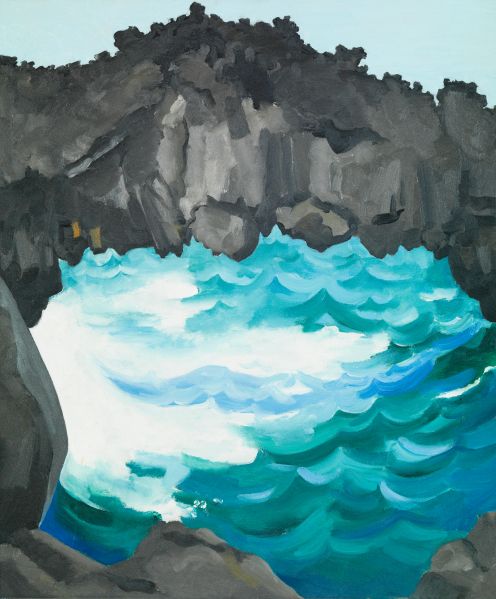

So it stands to reason that O’Keeffe’s verdantly virgin landscapes like Waterfall No. 1, ‘Íao Valley, Maui are more than visually enrapturing, but ultimately emblematic of an imagined past. They are an idealized abstraction of a land beset by colonialist enterprise that helps us forget our environmental callousness. To her credit, though, O’Keeffe seems to have realized that the otherworldly beauty of the islands she glimpsed, however partially or briefly, was an unnatural, commercialized illusion—one she was perhaps uncomfortably complicit in crafting. In her artist’s statement for the 1940 exhibition of the Hawaiian series, she wrote, “If my painting is what I have to give back to the world for what the world gives to me, I may say that these paintings are what I have to give at present for what three months in Hawaii gave to me…Maybe the new place enlarges one’s world a little. Maybe one takes one’s own world along and cannot see anything else.”